Apart from the roar of passing vehicles – ‘grey nomads’ rushing to their next sacred site – the land was mostly still and quiet. It was winter in the south and the air was bone-chillingly cold.

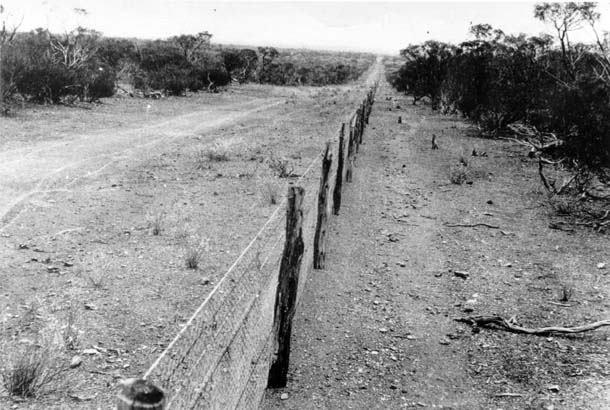

Mum and I were travelling from Adelaide to Darwin with a small tour group. We had tasted the tangy sustenance of saltbush. We tiptoed over pink salt lakes, fossicked in opal rubble and stomped in red dust. We gaped at an overturned car and caravan – burnt-out only thirty minutes before our drive-by. We visited a section of the Dingo Fence and tried to imagine the life of a boundary rider.

So, while covering a long straight section of the Stuart Highway, Rabbit Proof Fence seemed a fitting DVD diversion from the monotony of oxidised sandstone, silver spinifex and bitumen.

Set in 1931, the story refers to the physical barrier that was created to keep the pests from the east out of pastoral land in Western Australia. Three young girls are forcibly removed from their aboriginal mother and taken to Moore River Native Settlement Camp. This is a place of “re-education” to western ways and they are to be trained as house servants for well-to-do white employers. Government policy of the day actually believes it is helping these people. However, the girls escape to make a perilous 1500 kilometre journey back to their mother, home and traditional way of life.

As contemporary viewers (the movie was directed by Philip Noyce and released in 2002) we scoffed and scorned at the misguided authority of that day and the impact it had on those families and children. And we were shocked to learn via the credits that Molly and her mum only avoided re-capture back then by disappearing further inland.

Although the movie, a true story, highlights without mawkishness the trauma of the stolen generation, I cried as I watched the children scrambling for a view of their desperate mother; her hopeless running with the car that was taking them away; and then their family’s gut-wrenching wailing.

I marvelled at the gutsy determination of the young girls, particularly Molly, who had outwitted the law and, it seemed, the aboriginal tracker, Moodoo, while following the rabbit-proof fence home to their mothers.

But it was Molly’s heartbreaking admission, upon returning, of “losing one” that stirred me the most.

***

After fish and chips at the bustling Daly Waters Historic Pub, and a dip in the Mataranka Thermal Pool known for its 30 degrees Celsius warm springs that pump out 30.5 megalitres of water each day, some of us reconvened to the bus, with wine in hand, to watch another film. By this time, we were easily identifying with themes of isolation and hardship and We of the Never Never seemed another good choice.

This film was shot on location in the Northern Territory in 1982. The heroine, Jeannie Gunn was the first white woman to settle in the Mataranka area some 483 kilometres (300 miles) south of Darwin. She might have appeared out of place then amidst the thunderous cattle mobs and stampeding horses. But she demonstrated a no-nonsense attitude towards her new husband, the uneasy stockmen and the challenging chef, as she got on with tasks at hand and attended the sick and marginalised around their home at Elsey station. It is an inspiring story, which was later embraced by Australian schools.

It was the perfect film while visiting Elsey National Park, even though some of the language and ideas are out-dated. Yet as Mum and I travelled across the wide-open space – the never never – we realised more and more that the outback of today is still a great mystery. We noticed a broad range of people working in various roles for the information and cultural centres, but also other places where shop windows were barred and security was high. And we saw people walking the streets with ostensibly nothing to do, while others were hooked to their mobiles, distracted and oblivious.

We tourists, rushing like ants in the red dust along our busy highways, barely register the breadth and depth of this amazing land. We try, sometimes in vain, to understand Australia’s heritage, and its issues with distance, but one thing we do grasp is the invitation made loud and clear from it’s “First Peoples” to share the country: to visit, to get amongst it and to absorb its ageless stories.

I had seen these films before our trip, but viewing them within the context of the land gave them extraordinary power. I became closer to the characters and their stories, and ultimately more open to indigenous culture and land rights.

Now more than ever we need our film industry to deepen the connection between our unique country and its surprising inhabitants – grey nomads included!

Fabulous post Julie. I can just imagine being with you on the journey

LikeLike

Thanks Sue. The more I think about that trip, the more I appreciate it.

LikeLike

Lovely words Julie, you evoked our wide land beautifully.

LikeLike

Thanks Deb. The Kimberleys are calling me now …!

LikeLike

Like your writing butcherbird. Very readable. Need more. Penny

LikeLike

Thanks Pen.

LikeLike

I could feel the dust and taste the saltbush in your writing. That photo at the end is a true representation of the split between those ‘first peoples’ and us. May enormous goodwill bring the two halves together.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Julie, your writing and review of this most important story, is a wonderful read. I love how you bring along your experience in that harsh landscape. The book is a must read for us all. I also read about Molly being stolen with her 2 children later on. The tragedy in these stories is overwhelming. I have just seen the movie “The song keepers” which tells the story of the Aboriginal Women’s Choir from Hermansburg mission near Alice Springs. What an amazing achievement.

Mira

LikeLike

Thank you Mira. I really appreciate your support of my writing.

That trip with my mother was important in so many ways.

I will definitely follow up on this movie too. Thank you again.

Julie

LikeLike